Students study New Orleans’ rich life and tenuous landscape

The class “The Port of New Orleans: Culture and Climate Change” focuses on how the global climate problems of tomorrow imperil New Orleans today, and how people and culture can affect change. The course encompasses PEI’s Grand Challenges and summer internship programs, as well as the Program in Environmental Studies and the Environmental Humanities at Princeton initiative.

As Lavinia Liang watched a sultry wind ripple the brackish expanse of Bayou Bienvenue, its sparkling surface stippled by the muted reflections of withered cypress stumps, she understood how nature and relentless human error can unwittingly conspire to kill a place. Maybe even a whole planet.

The bayou’s dense cypress forest once helped protect New Orleans’ Lower Ninth Ward from storms and storm surges from the Gulf of Mexico. But the now-closed Mississippi River-Gulf Outlet Canal — a 1960s blunder known locally as “Mr. GO” — drowned the forest with salt water. In 2005, after 40 years of accelerating the loss of protective marshes and forests, the canal provided an unobstructed path for Hurricane Katrina and the storm surge that obliterated the Ninth Ward.

“Even though New Orleans has always been at the mercy of its environment, there’s an urgency to it today,” said Liang, a Princeton University senior and politics major. “To see that the environment can be an antagonistic force in Louisiana was disappointing and even heartbreaking at times, but the resilience of the city is such that I’m also hopeful.”

Liang went to New Orleans during spring break with her class, “The Port of New Orleans: Culture and Climate Change,” taught by PEI associated faculty Jeff Whetstone, a professor of visual arts in the Lewis Center for the Arts. The class stems from Whetstone’s project funded by Princeton Environmental Institute, “Flow: Living with the Mississippi,” which focuses on climate and the fate of New Orleans.

The class focuses on the perilous relationship New Orleans has had with nature and how the city’s people and culture have adapted to a fluid (often literally) landscape. That relationship has become more fraught as southern Louisiana faces fiercer storms, sea-level rise and unfathomable land subsidence — Manhattan-sized chunks of the Louisiana coast vanish every year.

But the course is not just about New Orleans, Whetstone said. It’s about witnessing today the potential future of a world altered by climate change, from land loss to the disproportionate brunt borne by minorities and the poor. Louisiana is even the site of the first government-funded evacuation based on climate change, Whetstone said. The state and federal governments are working to evacuate residents of Isle de Jean Charles, which was home to a band of Biloxi-Chitimacha-Choctaw Indians for nearly 200 years.

“We’re seeing the climate-change dynamic play out in New Orleans in fast forward,” Whetstone said. “New Orleans is 50 years ahead of all other cities, including Miami. It’s sinking and that mimics sea-level rise. It’s actually sinking faster than sea-level rise.

“When I was working on ‘Flow,’ I got access to all kinds of things that are usually inaccessible [such as the Port of New Orleans],” Whetstone said. “I thought, ‘If students at Princeton could witness some of this really complicated environment, landscape and culture, it could stimulate them to develop some sort of solution to the problem.'”

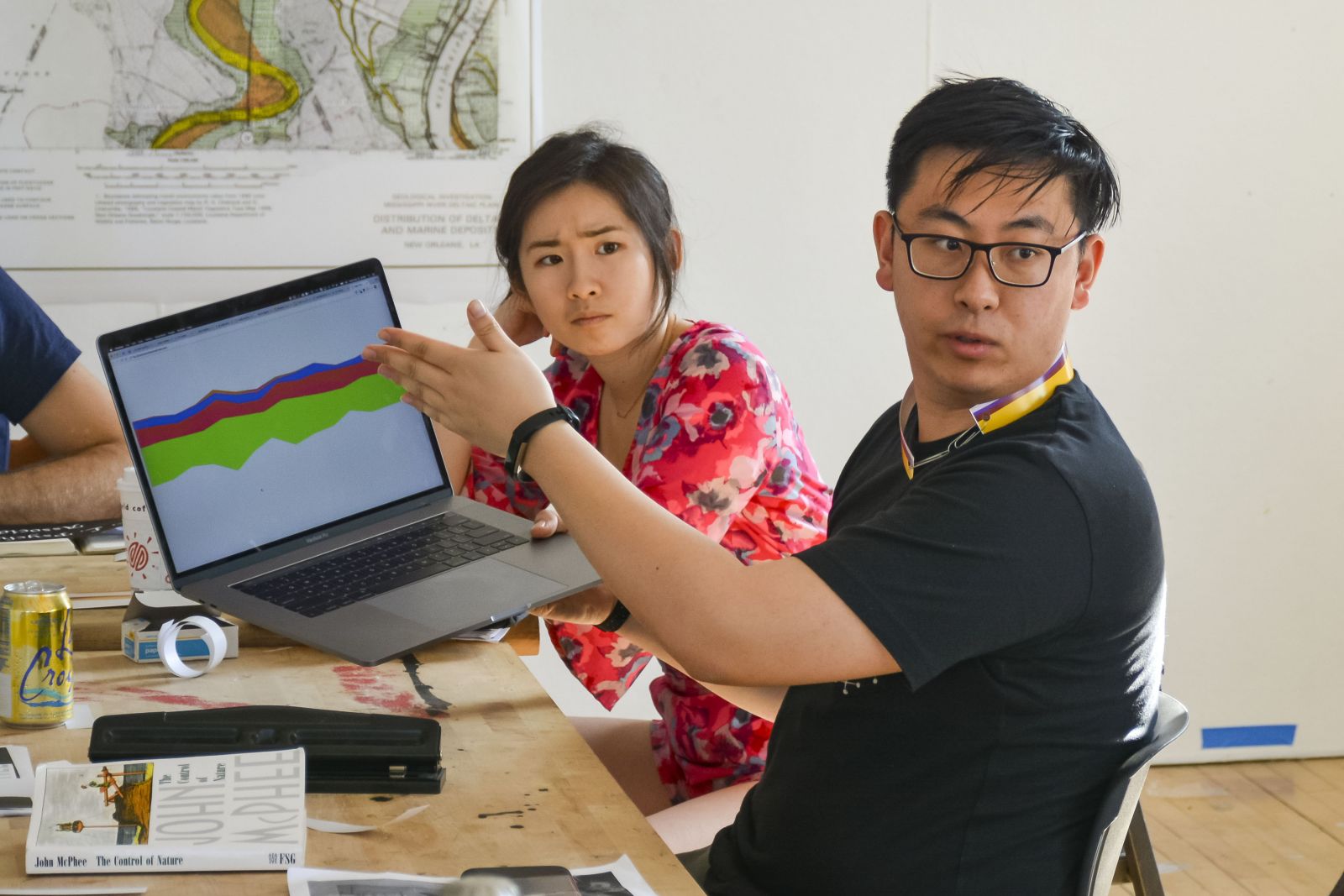

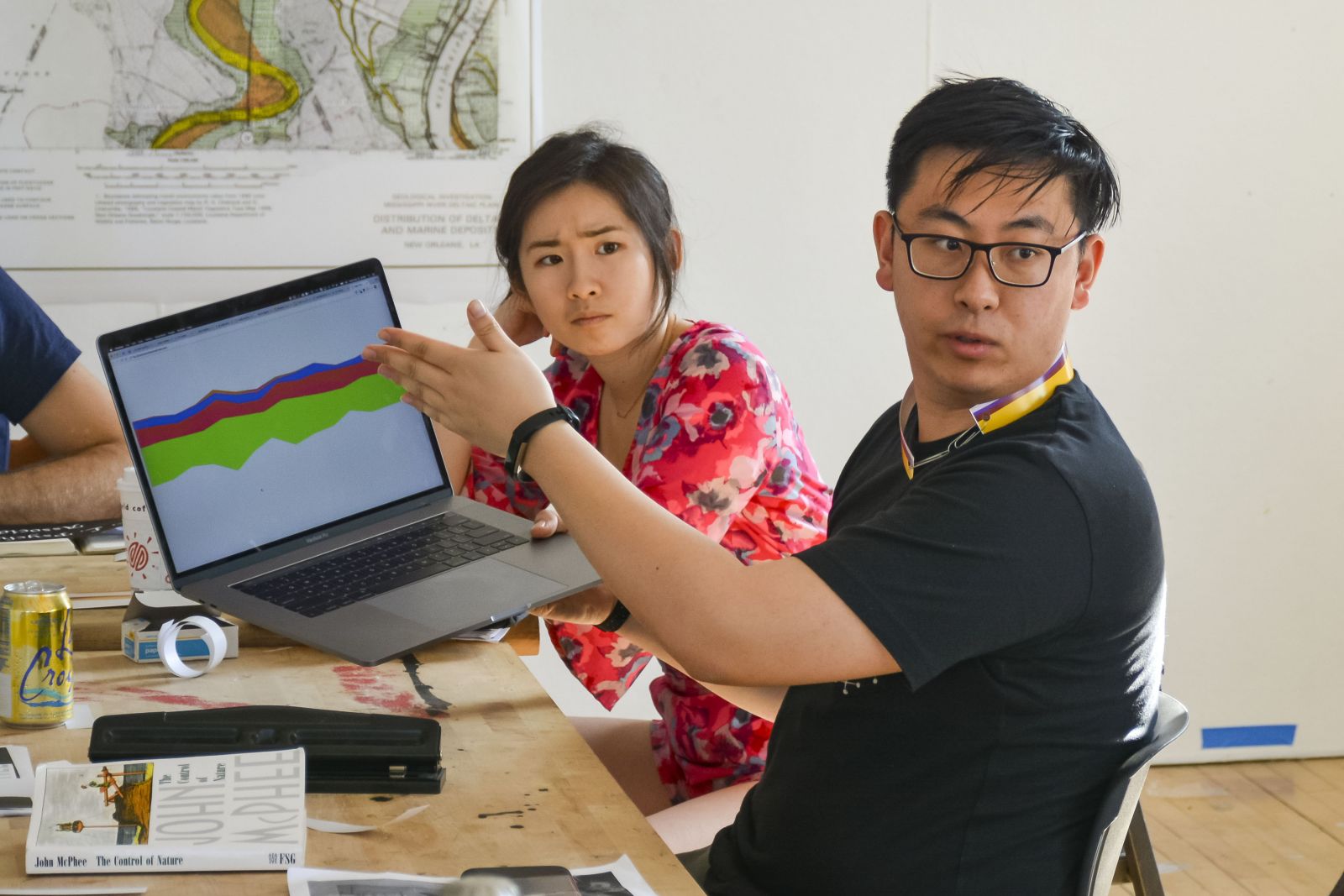

Senior Eric Li, who is majoring in computer science with a minor in visual arts, said that he was not fully cognizant of the climate problem before he saw it firsthand in Louisiana.

“Climate change for most of us is incredibly abstract,” Li said. “We all know it happens and we all know we need to do something about it. But the scale and degree to which it is happening in New Orleans paints such a sobering reality that it forces us to really contend with something, even if we already knew it was happening.”

“Catastrophes happen and you deal with them, but you never expect the one slowly coming,” said Angélica Vielma, a senior majoring in visual arts and advised by Whetstone. Vielma spent eight weeks in New Orleans during summer 2017 working with Whetstone as a PEI intern on his documentary about life on the lower Mississippi, “The Batture Ritual.” The film screened at the 2017 Prospect New Orleans art festival.

“People in New Orleans know what’s happening — they know there’s more flooding and that the land is subsiding,” she said. “These kinds of things are going to keep happening because the world is changing and people aren’t adapting quickly enough.

Students in the class studied the history, culture, politics and infrastructure of New Orleans to understand how people can cope with environmental changes — or make them worse. The class read books about the city’s 300-year face-off with the soft, low-lying land beneath it, including “The Control of Nature” by John McPhee, Princeton’s Ferris Professor of Journalism. During their trip to New Orleans, students toured the levees that constrain the Mississippi River and prevent it from rebuilding the land with silt. They visited the Gulf Intracoastal Waterway West Closure Complex built after Katrina and contains the largest water pump in the world.

“The reason that the river’s natural course cannot be allowed to run its course is because of these forces of American capitalism,” said senior Lachlan Kermode. “There are economic and sociopolitical forces that need nature to take a different course.”

The class also hosted numerous artists from New Orleans who discussed the influence of the land on local art and culture. Visitors included two Mardi Gras Indian chiefs who visited campus in April and whose tradition pays homage to the Native Americans in the marshes surrounding New Orleans who provided refuge for runaway slaves.

For their final project, students will translate what they learned into a proposal for an art project that would present a vision of the city’s future — a “New” New Orleans — that is relevant to the city and landscape.

“New Orleans is a city about improvisation,” Whetstone said. “Certain things work there that wouldn’t work in another city. You can see how in this spongy, weather-torn fecund place improvisation is necessary. You’re continually rebuilding and reshaping as the land is rebuilding and reshaping itself.

“The goal of this course was to look at southern Louisiana scientifically, culturally and environmentally at the same time,” he said. “I have a feeling that art is a way to braid together all those endeavors and make them communicate. The class is an art experience about environmental data.”

Art can transform data into something that moves people to take action, Vielma said. “Jeff’s push for art and science to come together is inspiring to watch and it’s something I want to be a part of,” Vielma said. “People don’t appreciate how much aesthetics impact people’s everyday decisions. You can have all the data in the world, but if you don’t have a sufficient way to communicate them, then it’s not any good to anybody. That’s where art comes in.”

The course has demonstrated that the arts can serve a role in an environmental crisis frequently framed in scientific and political terms, said Liang, whose independent work at Princeton focuses on state sponsorship of the arts.

“My interest and knowledge of environmental justice was purely on the personal scale,” Liang said. “When I saw this class, everything seemed to click. I was hungry to learn more about how I could be more involved, and this class recognized how those involved in the arts can be effective agents in all of this. People aren’t convinced by political rhetoric and others telling them what to do or what’s right. They need to feel it themselves. That’s where cultural elements come in.”

The past and present of New Orleans, Li said, emphasizes the importance of scientists and engineers being able to identify with the people and cultures they intend to help.

“This class revealed to me that more often than not we do not think about the cultural implications of scientific and engineering efforts,” Li said. Yet, “most of these efforts are done in part to save a culture and city. The fact that engineers can graduate from Princeton without receiving a class in the ethics and humanist effects of their work is very problematic, and one that I think that this class attempts to resolve.”

In the end, Whetstone said, the class focuses on the unique culture of New Orleans — and its distinct risk of disappearing forever — to accentuate the importance of not only saving places, but also the people they create and that define them.

“The most efficient way to deal with New Orleans is to forget about it — pull up stakes and let it go,” Whetstone said. “But if we do that, we lose a symbol of some of the great things about this country and the world in a time when we need it most.

“To find strength in diversity and improvisation, that’s what New Orleans is,” he said. “If we give up on that, we might as well give up.”