Saving our cities and ourselves: A Q&A with PEI’s Ashley Dawson

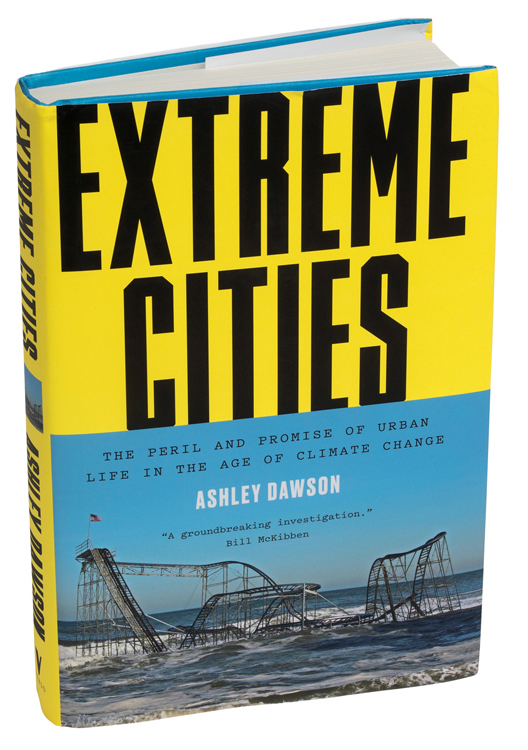

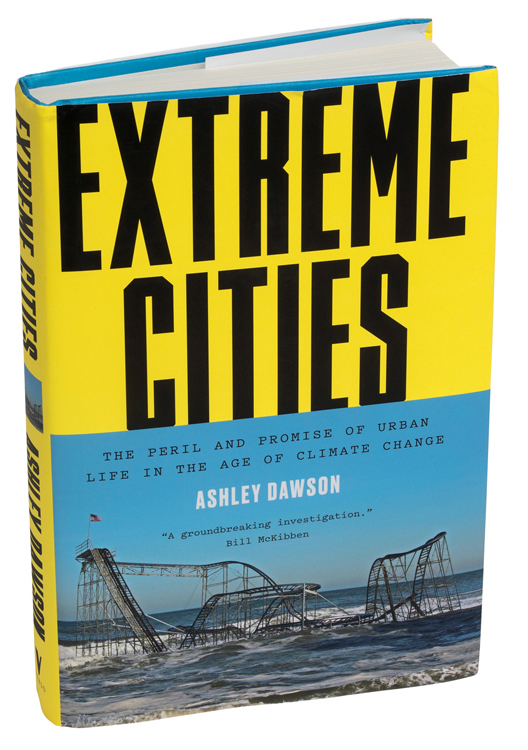

Eco-justice scholar and activist Ashley Dawson, PEI’s 2017-18 Barron Visiting Professor in the Environment and the Humanities, spoke with PEI about his recent book, “Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change,” the uncertain future of cities, and how we can save our largest and most imperiled communities.

By Morgan Kelly, Princeton Environmental Institute

Eco-justice scholar and activist Ashley Dawson, the Princeton Environmental Institute’s 2017-18 Barron Visiting Professor in the Environment and the Humanities, delves into the uncertain future of cities worldwide in his recent book, “Extreme Cities: The Peril and Promise of Urban Life in the Age of Climate Change” (Verso). “Extreme Cities” has recently been featured in The Baffler, Longreads and Maclean’s, as well as the Politics & Polls podcast produced by the Woodrow Wilson School of Public and International Affairs.

[Related: Dawson will discuss “Extreme Cities” with Thanu Yakupitiyage, U.S. Communications Manager for 350.org, at 6 p.m. Wed., March 14, at Labyrinth Books in Princeton.]

Named one of the ten best books of 2017 by Publishers Weekly and Planetizen, “Extreme Cities” analyzes the legacies of injustice and short-sighted profligacy that imperil our cities and our planet. But, more importantly, he spotlights the efforts of politicians, scientists, architects, engineers and motivated citizens to slow the destruction, fight for equality, and ensure that the world’s cities — and the people in them — survive into the next century. As Dawson writes, the future is about “fighting for the city as it may be rather than the city as it currently exists, the good city of the future rather than the extreme city of the present.”

In the interview below, Dawson discussed with PEI the work that went into writing “Extreme Cities,” the revelations he got from the experience, and what human society can do from here.

Princeton Environmental Institute: What motivated you to write this book and how did you research it?

PEI: How did you research this topic and what overlying theme did you uncover?

Dawson: My research exposed both the great vulnerability of contemporary cities, as well as the exciting and innovative efforts to cope with it. I dove into the scientific and sociological literature on climate change and natural disasters. I wanted to understand the cutting-edge scientific research on these topics, but also learn how different people react to urban precariousness. I met with architects experimenting with new forms of “living infrastructures” to protect coastal communities from storm surges. I also met with the heroes in the environmental-justice movement who are struggling to clean up their own communities, and with the people organizing grassroots resiliency plans that push cities to transition away from their current, unsustainable forms.

PEI: How would you characterize current efforts and campaigns related to sustainability, ‘green’ living and urban resilience?

Dawson: There is a lot of ferment right now around urban adaptation to climate change. In “Extreme Cities,” I discuss some of the climate-proofing projects developed in New York after Sandy and I connect them to efforts undertaken in places such as the Netherlands. They are certainly to be celebrated. They recognize that climate change is actually happening, that it will intensify, and that cities must respond. Some measures are relatively traditional, such as building sea walls, but some are far more visionary, such as green roofs and walls, parks that double as water-containment zones, and wetland catchment zones.

But these efforts are militated against by an unsustainable capitalist system predicated on incessant growth. In the book, I show how planetary urbanization is a product of this economic system’s need to find a sink for excess capital, which has led to the growth of cities in flood-prone coastal areas. The economic system that is dominant today — in both material and ideological terms — is profoundly irrational. If we are to address the climate crisis in a genuine and fundamental way, we must confront and overcome an economic system predicated on feckless, headlong growth.

PEI: How does modern capitalism differ from the capitalist structure of the past, which also was highly destructive?

Dawson: Capitalism and cities have gone global in the past 40 years. In the recent past, only the industrialized nations of Western Europe and North America had the majority of their citizenry living in cities. Most people in the world lived in the countryside. Now, the majority of humanity lives in cities, and most of those cities are in once-rural, formerly colonized countries. Ninety percent of urban population growth this century will take place in Africa and Asia. These growing cities will be the place where humanity solves climate change, or fails to do so. As the global South urbanizes, we cannot afford to keep building the sprawling, segregated cities that characterize the United States. Compact cities with plentiful public amenities and an abundant living infrastructure such as green roofs — cities that physically resemble Singapore more than Houston — offer a way forward for our urban future.

PEI: To what extent do industrialized nations perpetuate unsustainable urban growth, and how are these nations in a position to make cities less vulnerable?

Dawson: There is a strong element of coercion behind contemporary urbanization that doesn’t get acknowledged enough. Neoliberal policies of globalization — such as free-trade agreements — have mandated dramatic cuts in protective tariffs in many developing countries. As a result, these countries have been swamped with cheap agricultural products from developed countries where agriculture is mechanized and fossil fueled. This has driven millions of peasants off the land and into mega-cities such as Mexico City, Lagos and Dhaka. It would be nice if one could argue that the world’s richest and most powerful nations are now leading the way to more sustainable forms of the urbanization, but that is manifestly not the case. The United States has dropped out of global carbon-mitigation efforts and European Union countries — while far more progressive in cutting their own emissions — have not committed nearly enough to helping developing countries pursue low- to zero-carbon economies.

PEI: How does economic inequality exacerbate the natural threats from climate change, and why is that not a bigger part of the climate change conversation?

Dawson: Inequality is the principal challenge facing cities in this risky new world. Natural disasters tend to magnify gaping economic and social injustices. But this iniquity is easier to perpetuate because of the relative insulation from climate chaos that wealthy individuals and societies enjoy. Hurricane Harvey inflicted significant damage to Houston, but this damage was mild in comparison with the almost total social collapse that Hurricane Maria caused in Puerto Rico. The most sustainable cities are the ones with the most social solidarity, but the global economy generates cities in which the one percent live in glittering splendor while the great majority of people live in increasingly disastrous poverty. If we wish to make our cities resilient, we must tackle this lop-sided economic system.

PEI: In your chapter on “disaster communism,” you discuss how disaster can overcome inequality and stratification. What will it take for that dynamic to more become commonplace?

Dawson: Disasters often bring out the best in people. Crises can elicit forms of heroic selflessness, social connection and community-building. My research looked at the kinds of solidarity that emerged in New York City during and after Superstorm Sandy, including the Occupy Sandy network. I spoke with activists who went door-to-door in devastated communities and helped people find shelter, food and medicine, often while facing their own struggles to survive. Making such forms of collective mobilization and solidarity more commonplace is the great challenge of our times.

PEI: What do you see as the obstacles to public solidarity on addressing climate change?

Dawson: We have all the technology we need to establish equitable and sustainable carbon-neutral societies. What we lack is the political will and collective imagination. This is largely a product of how the rich in general — and fossil fuel companies in particular — have corrupted and smashed genuine democracy. These firms have known about climate change for decades, yet continue to spread disinformation about climate change. Most recently, they pushed their minions in the administration of President Donald Trump to open all American coastal areas to a new and suicidal round of oil and gas extraction. To fix the climate problem and save the planet, we must take back and revive our democracies.

PEI: What is needed to curtail further climate change and what progress has been made?

Dawson: We need a just transition to a post-fossil fuel society. Every level of government should be planning to transition to zero carbon emissions by 2050. These plans should have credible stages, should not leave the hardest steps for last, and should include provisions that help workers in fossil fuel-based industries find well-paying employment in renewable-energy industries. Right now, the future certainly looks bleak, but there are many challenges to these destructive trends. The fight against new fossil fuel infrastructures won a huge victory in January when New York Mayor Bill de Blasio announced that the city would divest its public pension funds from all fossil fuel-related investments, and that it would sue the five biggest fossil fuel corporations. The nation’s biggest and richest city is taking on the world’s biggest and most irresponsible industry! New York’s stirring challenge suggests that we may have arrived at a historic turning point in the struggle to avert global climate catastrophe.