‘Defend the progress you’ve made’: Addressing the urgency, hope of conservation

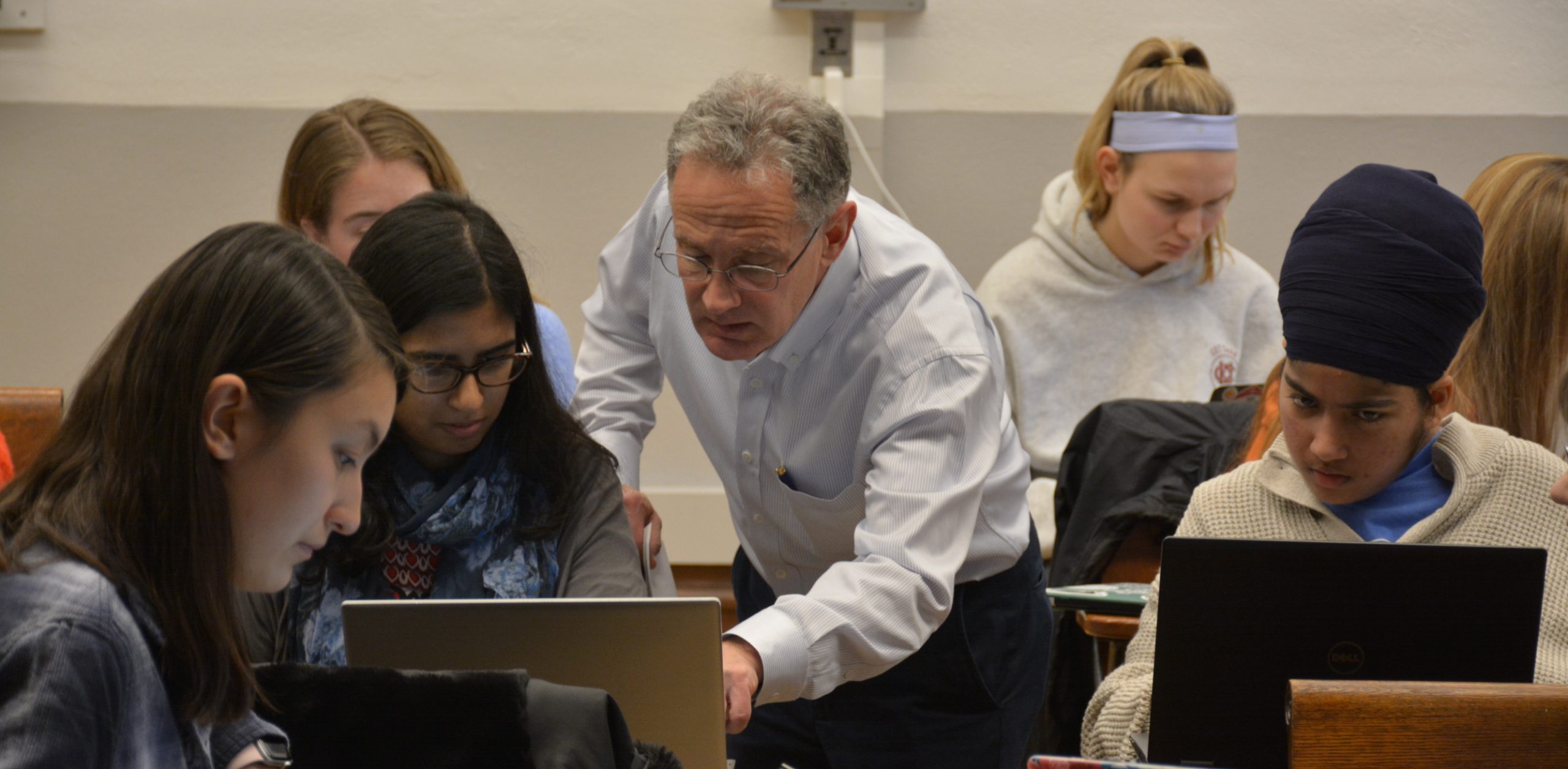

“How many of you have found the content of this course depressing?” Princeton professor David Wilcove asked as he began one of the last lectures of the fall course “Conservation Biology.”

After three months of examining the global decimation of wildlife and ecosystems caused by development, agriculture, industry, climate change and invasive species, most of the students raised their hands. “Pretty depressing,” senior and ecology and evolutionary biology major Olivia Sheppard said with dry emphasis.

“That’s why I like to include a lecture on restoration ecology to provide a glimmer of hope,” Wilcove, a professor of ecology and evolutionary biology and public affairs and the Princeton Environmental Institute, told the undergraduates as he detailed the efforts that people have undertaken to replace and rejuvenate natural lands.

A long-time course in Princeton’s ecology and evolutionary biology and environmental studies curriculum, “Conservation Biology” teaches students how to identify — and possibly mitigate — the effect of human activities on species and natural ecosystems.

“Each year, I’m tinkering with the balance of the natural sciences and the social sciences to give students an optimum view of where conservation biology is headed and what the issues currently are,” said Wilcove, who taught the class for the third time last semester.

Wilcove realizes that students today live in a time when protecting species and habitats has hardly seemed more crucial — or more daunting.

“Students are justifiably dismayed at the state of the global environment. More worrying is that they’re also dismayed at their prospects for changing the status quo — that is something I hope to dispel,” Wilcove said after the class.

“There is a balance to accurately showing them the magnitude of the problem while conveying a sense that things can be better,” he said. “Everyone who teaches about the environment faces the same dilemma.

“I’ve been around long enough to know there are times you can make progress and times when you have to defend the progress you’ve made,” Wilcove said.

Vienna Lunking, a senior in ecology and evolutionary biology getting a certificate in environmental studies, said that Wilcove’s focus on successful conservation — such as the reintroduction of gray wolves to the American West, or the ongoing stabilization of the Florida panther population — improved her outlook.

“Much of the course has echoed some of the more depressing things of which I was already aware, so it was encouraging to hear about positive impacts actually being made,” said Lunking, who plans to become a veterinarian and is president of the Princeton Pre-Veterinary Society.

Nonetheless, Lunking wondered if the challenges facing the environment are too big. Students in the course broke into groups to study specific topics, species and ecosystems. Lunking’s group focused on alternative conservation methods for protecting polar bears and other species threatened by climate change in light of humanity’s failure to halt climate change itself.

“It seems unlikely we’ll be able to save most climate-threatened species without addressing global warming, and even if we were able to dedicate the enormous resources and efforts to conserve a few charismatic species, there’s no way we could do this for the vast majority that are facing extinction,” Lunking said.

“I struggle with the fact that many of the people who would benefit from a class like ‘Conservation Biology’ would actually be opposed to or have little interest in it,” Lunking said. “How do you teach this material to the climate deniers, developers, industrialists and others who are in need of a wake-up call?”

Junior Rimsha Malik worked on a project that studied the reintroduction of wolves to Yellowstone National Park in the mid-1990s. The extirpation and subsequent return of wolves to the park resulted in ecosystem-wide changes that ecologists have since studied to understand how species are interrelated.

The Yellowstone wolves also highlight the social and political elements of conservation, said Malik, an ecology and evolutionary biology concentrator pursuing a certificate in neuroscience who plans to become a wildlife veterinarian. As a PEI intern at Kenya’s Mpala Research Centre last summer, Malik studied the effect of grass-based animal feed on the health of local livestock, as well as on the quality of rangeland and the well-being of wildlife.

“The class realistically discussed many social, political, economic and ethical aspects of conservation, and helped us understand the complexities that arise when trying to protect species. Simply laying out laws to protect a species may not be an easy fix,” Malik said.

“Conserving the world’s biodiversity depends on policymakers as much as it does on researchers,” she said. “Definitions, words and phrases are very important to consider when drafting conservation laws because without careful word choices there could be loopholes for individuals who do not support conserving biodiversity.”

Wilcove focuses on case studies that detail specific successes and failures in conservation, and the complications in between. These include restoration of the Tijuana River floodplain in San Diego, California, that overlooked the importance of the pathways that rodents — frequently hunted by nearby housecats — carve through the dense grassland allowing juvenile plants to grow. Also, China’s Grain-for-Green reforestation program that research from Wilcove’s group showed was replacing farmland with monoculture plantations devoid of wildlife instead of diverse native-tree forests that could support more species.

“Students are more likely to remember concepts if they’re associated with a story, which is essentially what a case study is,” Wilcove said. “While global trends are very important, local and national trends often tell a more complex and, sometimes, more helpful story.”

Senior Daniel Tjondro, a civil and environmental engineering concentrator pursuing certificates in environmental studies and urban studies, said the course provided a balance between his seemingly disparate academic interests — the built environment and the actual environment.

“Whereas many see development as the opponent of biodiversity, I’m interested in how the two can be reconciled,” Tjondro said. “From overfishing to logging, it wouldn’t be a stretch to say that human activities are doing more harm than good for the environment. But this class also taught me that through efforts such as the Endangered Species Act and quantifying ecosystem services, humans could also be the answer.”

A recent focus in conservation, “ecosystem services” refers to the benefits that human society receives from healthy, functioning ecosystems and abundant biodiversity, from medicine and food, to clean air and peaceful open spaces.

Framing conservation in human terms may be unavoidable, said junior Joe Kawalec, an ecology and evolutionary biology concentrator getting a certificate in environmental studies.

“Generally, preserving animals because they have a right to live is not an easy thing to convince someone about. People may value certain animals in their lives for a variety of personal reasons, including religious, spiritual and national identity reasons,” said Kawalec, who is part of the Princeton Conservation Society and the Princeton Birding Society.

“The obstacles to people conserving animals based on their intrinsic qualities range wildly, from a lack of personal connection with animals on a daily basis to people who mainly think in terms of rational financial decisions,” Kawalec said.

“Translating between languages of nature and society is an ongoing issue that is vital to convincing the general public about the importance of investing in our natural world,” he said.

An additional challenge is that, with each passing generation, the natural world as it once was becomes ever more distant, Wilcove told the class.

“When we say we want to restore an ecosystem, restore it to what?” Wilcove said.

“You create this mental picture of what things should be like, but that picture is different from what your parents have. Essentially, there’s a reset button in which each generation sees changes over time and wants to restore ecosystems to what they remember them as.”

“There are absolute limits on the degree to which we can restore any system. Constant vigilance and active management are necessary — you’ll never be able to restore a habitat and walk away,” he said.

“It’s harder to restore than to protect.”